Osgood-Schlatter syndrome (OSS) is a sports injury that affects 1 in 10 adolescents and even 1 in 5 young athletes.

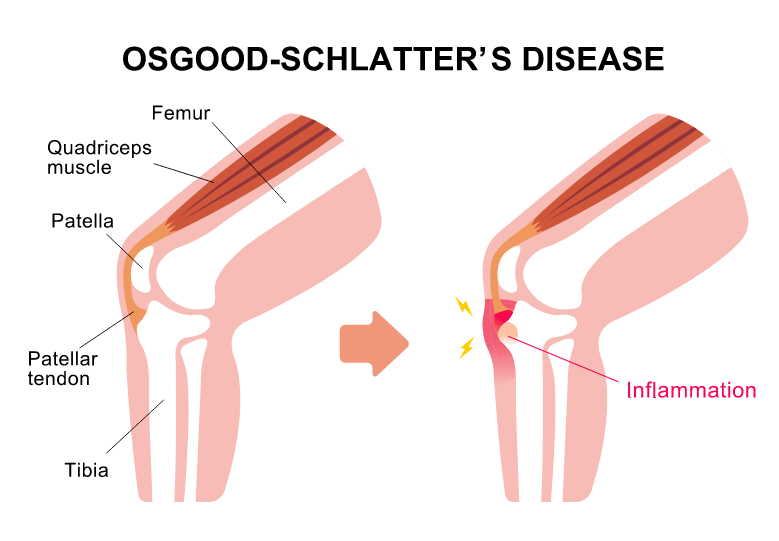

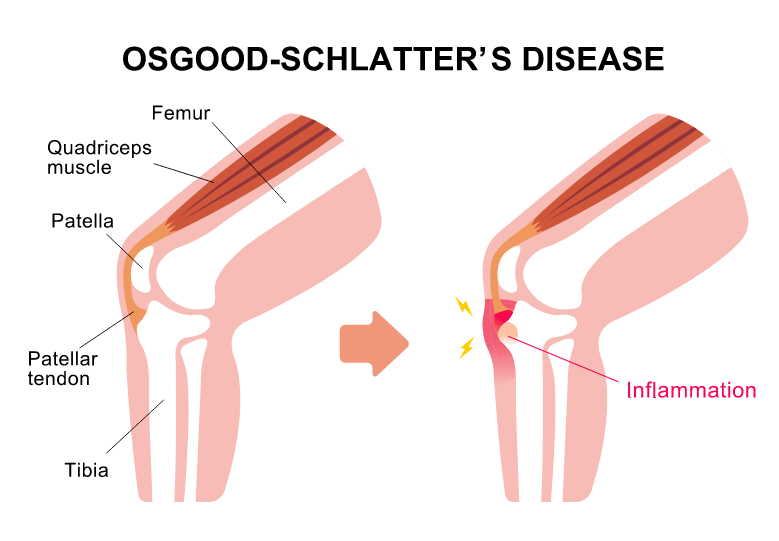

Osgood-Schlatter syndrome, or osteochondrosis, is an inflammation that affects the patellar ligament (i.e. the ligament that attaches the kneecap bone to the tibia bone) at its origin and inhibits normal bone growth.

In 25% of individuals, intermittent pain first occurs at the tibial ligament process, becoming more constant and intense over time. It is characterized by a sharp pain which increases with exertion (prolonged walking, stair walking, running, jumping). A bony protrusion often occurs alongside the pain.

Osgood-Schlatter syndrome develops in both knees in 20 to 30% of all adolescents.

Successful physiotherapy treatment focuses on reducing pain, strengthening the knee muscles, increasing mobility in the knee, establishing correct movement patterns and gait biomechanics.

Inadequate treatment of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome leads to instability in the knee and inability to load the leg (difficulty in walking). Approximately 10% of all individuals develop long-term symptoms that limit it in adulthood.

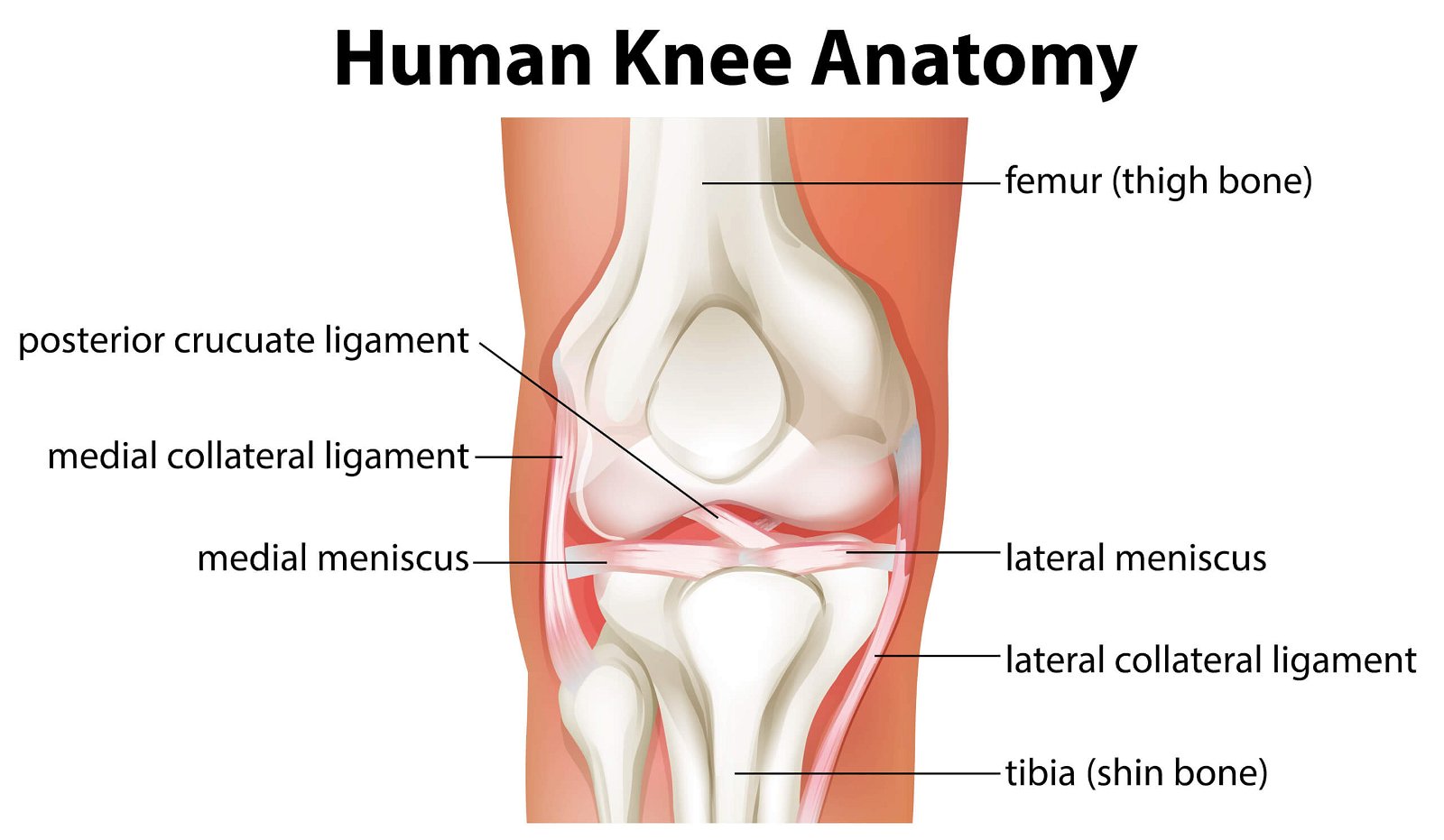

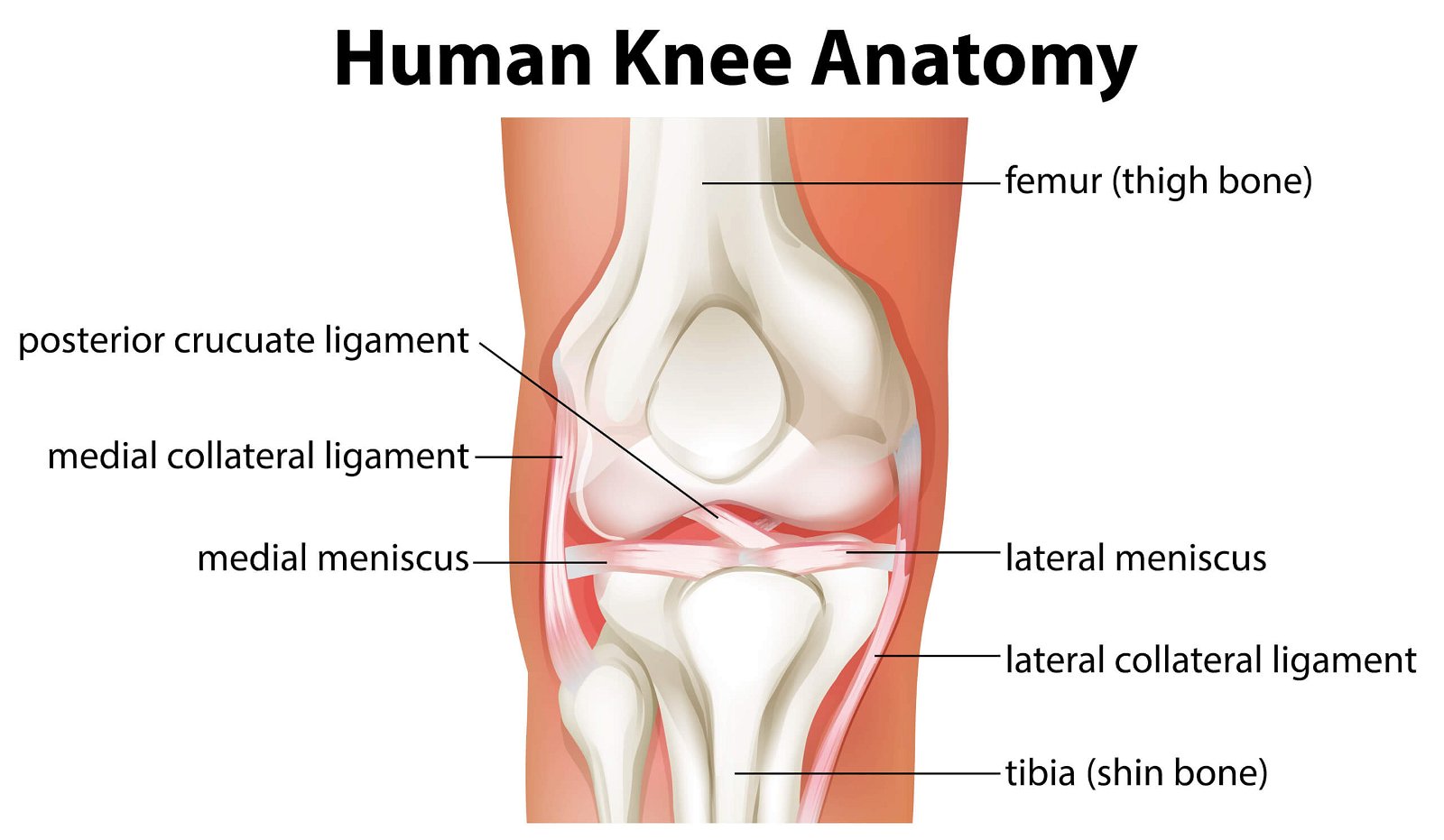

Anatomy of the knee joint

The knee joint is the most complete and complex joint in the human body.

It consists of two bones (femur and tibia) and three joints (tibiofemoral, patellofemoral and tibiofibular syndesmosis). The dynamic stability of the knee joint is provided by the muscles and the static stability is provided by the ligaments (anterior cruciate ligament, posterior cruciate ligament, internal collateral ligament and external collateral ligament).

A specific feature of the knee joint is the two menisci, which act as shock absorbers in the knee joint to facilitate the transfer of weight and load to the body.

The largest thigh muscle (m. Quadriceps) attaches to the tibia bone via the patella (lat. Patella) and the patellar ligament. The bony attachment site is called the tuberosity of the tibia, which develops, grows and strengthens over time during adolescence.

The main factors in the development of Osgood Schlatter syndrome

Osgood-Schlatter syndrome most commonly occurs at puberty during the growth phase in boys between the ages of 10 and 15 years and in girls between the ages of 8 and 13 years.

The syndrome occurs more rapidly in girls due to the processes of growing up, as they reach the bone growth phase two years earlier than boys (girls’ bones develop more rapidly).

OSS used to be more common in boys, but the difference in incidence between the sexes is decreasing.

Statistically, athletes most commonly affected are those in sports that require a lot of running and jumping, such as football, basketball, volleyball, gymnastics or ballet.

The main mechanism of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome is inflammation at the attachment of the patellar ligament to the tibia bone, where there is an area of “growth plate” that becomes thicker with growth.

It is caused by repetitive overloading, a strained patellar ligament, overgrowth, overweight, traumatic injury or tibial fracture.

A strained patellar ligament causes pain and a visible depression/bony bulge below the knee.

Repeated mechanical stretching of the ligament causes microvascular damage and inflammation, which results in swelling, pain, inflammation and tenderness to touch.

Prolonged microvascular damage and inflammation cause changes to the bone, which in 10% of individuals does not grow back properly. This condition is an indication for surgery due to the limiting pain.

The most common symptom of Osgood-Schlatter is sharp pain below the knee, which increases with exertion (walking, squatting, stair walking, running, sports activities) and decreases during rest.

It is characterised by a bony protrusion below the kneecap (on the tibia bone), which becomes swollen and sensitive to touch.

One of the symptoms of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome is overstretching of the muscles of the knee joint (the large thigh muscle, the posterior lodge – the “hamstrings” or calf muscle).

There are often problems with the balance of the body during functional activity.

Prolonged acute pain results in reduced daily functionality (performing sports activities) and impaired walking (or ‘limp’).

Symptoms are often present for 12 – 18 months.

Special diagnostic examination

The diagnostic physiotherapist performs a specialised diagnostic examination including anamnesis, history taking of the syndrome, functional status of the body, arthrokinematics assessment, muscle proportion and endurance, pain assessment, balance and coordination assessment, functional movement patterns and biomechanics of gait.

The diagnostic examination provides insight into the functioning of the body, the cause of the problem and the consequences caused by the condition.

Occasionally, diagnostic X-ray imaging is indicated to show inflammation in the initial phase of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome. Usually an X-ray is performed to exclude a fracture of the tibia, infection or bone tumour.

It is important to distinguish Osgood-Schlatter syndrome from other diseases affecting the knee joint, such as jumper’s knee, runner’s knee, patellar tendinitis and infrapatellar bursitis.

The diagnostic report is the basis for determining the individual physiotherapy programme.

Physiotherapy for Osgood-Schlatter syndrome

Acute phase

The acute phase of physiotherapy treatment primarily involves symptom control, with the aim of reducing pain and swelling caused by inflammation.

The acute phase of physiotherapy involves the use of cryotherapy, thermotherapy and isometric exercises (muscle activation to reduce pain), including the use of state-of-the-art technology.

TECAR therapy, PERISO therapy, HiTOP electrotherapy, LASER therapy and ultrasound therapy influence processes in the body that lead to faster tissue healing, reducing pain, swelling and inflammation.

In the acute phase of treatment, it is recommended to limit pain-inducing activities (including sports) and to rest actively.

Kinesiotaping is placed on the knee area to provide a more stable sensation and increase the lymphatic system function in daily activities. In certain individuals, a knee brace is also used, which is placed under the kneecap (for a feeling of stability during activities).

The acute phase of treatment lasts from a few days to a maximum of three months, followed by a sub-acute phase lasting three to six months. The chronic phase of treatment occurs after 6 months of coping with the symptoms and the disease.

The main muscular risks in individuals with Osgood-Schlatter syndrome are impaired flexibility of the large thigh muscles (m. Quadriceps) and the posterior thigh muscles (hamstrings). Pain occurs when performing passive and active knee flexion movements (flexion) and when adding resistance during knee extension movements (extension).

Joint strengthening

The next phase of physiotherapy treatment focuses on manual therapy, progressive exercise, stretching exercises (very important in case of shrinkage of the large thigh muscle and the posterior box) and strengthening of the dynamic stabilizers of the knee joint – the muscles. Progressive training means increasing the load of the exercises over time, so that the structures in the body are strengthened more quickly and efficiently and reach a higher level of function.

The kinesiology programme includes different forms of exercise (proprioceptive, neuromuscular and plyometric) for a quicker return to sport. Plyometric training is crucial in the treatment of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome before returning to sport as it requires the maximum activity (force) in the muscle to be achieved in the shortest possible time.

Preparation includes jumping, landing and fast running, which improve the reflex activation of the body and improve muscle function during the performance of sporting movements.

Physiotherapy treatment of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome is successfully carried out in 80% of football players at the same time as normal club training, despite the presence of symptoms.

Special sport treatment

Basketball players return to the court without symptoms of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome after 6 months of physiotherapy treatment.

Physiotherapy treatment for Osgood-Schlatter syndrome is long term (lasting from a few months to several years), but individuals return to sports training more quickly with pain reduction and proper progressive training.

Conditioning for return to sport and a preventive kinesiological training programme prepare the athlete to resume sporting activities in better shape than before the injury occurred.

Osgood-Schlatter syndrome is a long-term condition that resolves in most cases within up to two years.

It occurs most often in adolescents, and is particularly common in those who train for sports that require a lot of explosive movements, running and jumping.

Athletes describe a sharp pain below the knee, which increases during sporting activities and gradually subsides during rest. The pain is accompanied by symptoms of muscle shrinkage, swelling, bony protrusion and tenderness to touch.

Girls are affected more quickly than boys because of the earlier transition to puberty.

It is most often treated conservatively by physiotherapy, rarely requiring surgery. The primary phase of treatment involves a diagnostic examination and confirmation of the correct diagnosis. The diagnostic report gives insight into the symptoms and limitations of the body.

Physiotherapy treatment of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome focuses on eliminating the symptoms and causes of the disease through manual therapy, progressive specialized exercise (isometric exercises, strengthening exercises, mobilization exercises, balance exercises, plyometric exercise), the use of instrumentation and kinesiotaping.

We guide each individual from the onset of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome symptoms to peak fitness for return to sport.

- Vaishya R, Azizi AT, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Apophysitis of the Tibial Tuberosity (Osgood-Schlatter Disease): A Review. Cureus. 2016 Sep 13;8(9):e780. doi: 10.7759/cureus.780. PMID: 27752406; PMCID: PMC5063719.

- Neuhaus, C., Appenzeller-Herzog, C., & Faude, O. (2021). A systematic review on conservative treatment options for OSGOOD-Schlatter disease. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine, 49, 178–187.

- Smith JM, Varacallo M. Osgood Schlatter Disease. [Updated 2022 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441995/

- Kelc R., 2018. Anatomija in klinični pregled kolenskega sklepa. In: Koleno v ortopediji. XIV Mariborsko ortopedsko srečanje. Maribor: Univerzitetni klinični center Maribor, 13-22.

- Çakmak, S., Tekin, L. & Akarsu, S. Long-term outcome of Osgood-Schlatter disease: not always favorable. Rheumatol Int34, 135–136 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-012-2592-0

- Corbi F, Matas S, Álvarez-Herms J, Sitko S, Baiget E, Reverter-Masia J, López-Laval I. Osgood-Schlatter Disease: Appearance, Diagnosis and Treatment: A Narrative Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 May 30;10(6):1011. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10061011. PMID: 35742062; PMCID: PMC9222654.

- Jakovljević, Aleksandar & Grubor, Predrag & Simovic, Slobodan & Bijelic, Snezana & Maran, Milorad & Kalacun, Dario. (2010). Osgood Schlatter’s disease in young basketball players. Sportlogia. 6. 74-80. 10.5550/sgia.1002074.

- Osgood-Schlatter Disease in youth elite football: Minimal time-loss and no association with clinical and ultrasonographic factors. (2022, March 9). Osgood-Schlatter Disease in Youth Elite Football: Minimal Time-loss and No Association With Clinical and Ultrasonographic Factors – ScienceDirect. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from Science Direct.